Archival Silences

No archive is perfectly comprehensive. We learn not only from the sources that are present, but also by critically considering archival silences and absences. What sources are not here? Whose voices are not represented? What topics may be unwritten?

Prison policies and practices limit incarcerated people’s freedom of expression, shaping prominent silences in the American Prison Writing Archive. Explicit policies allow monitoring and censoring of incarcerated people’s communications, and unwritten practices of intimidation and retaliation create a chilling effect that discourages writing openly. As the Prison Policy Initiative notes in their research on prison journalism, the limited ability to maintain personal property while incarcerated can also limit the ability to write: “Papers, notes, books, and other materials that can be important to reporting are vulnerable to confiscation and destruction by prison officials during cell searches and transfers.”

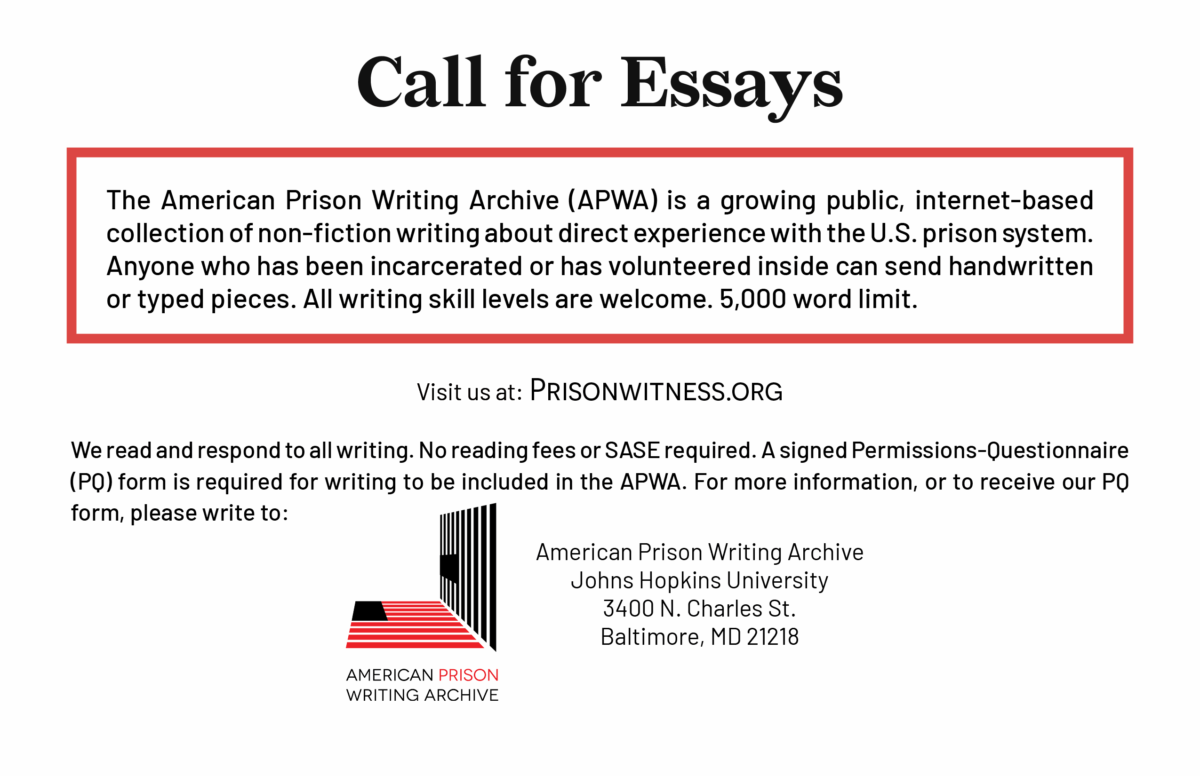

Limits on access to information, including book bans, limit the ability to consult reference materials and learn about writing opportunities. When access to periodicals the APWA advertises in, such as Prison Legal News, is limited, potential authors may never learn about the Archive. Policies and practices can change quickly and be enforced unevenly, and they differ across states, prison systems, and facilities.

Gender disparities in the APWA’s collection – featuring proportionally more writing by men than by women – in part reflect the unequal educational opportunities and resources available in women’s prisons. As the Chronicle of Higher Education has reported, women’s prisons have long been overlooked by prison education programs and frequently offer many fewer courses and programs than are available in men’s prisons. People in prisons lacking educational programs and resources may be less likely to learn about the Archive.

Differences between states are reflected in the APWA’s collection through uneven geographic coverage. For example, California and Florida have two of the largest state prison systems in the U.S. As of 2023, the APWA’s collection holds about nine times more writings from California than from Florida. Among other factors that differ from California, the Florida Department of Corrections is known for the nation’s most expansive prison book bans, banning over 20,000 titles, and also imposes privatized mail scanning, which limits privacy and access to postal mail. California also offers higher education programs in many more of its prisons than does Florida.

Even in states well-represented in the APWA’s collection, community advocacy has been necessary for incarcerated people to retain some level of access to free expression. For example, a recent policy to restrict journalism from inside New York prisons went largely unnoticed until New York Focus brought it to the attention of several national criminal justice journalism groups, such as The Marshall Project, which then acted quickly (and successfully) to advocate for the policy’s rescinding.

Silences are also reflected in the kinds of experiences reflected in the APWA. For instance, prisons may restrict or punish incarcerated people for publicly communicating about particular topics, such as prison conditions. Incarcerated people may also self-censor in order to manage potential risk to their immediate safety, release dates, parole, or future employment. People incarcerated for long periods of time may feel that they have “less to lose” by writing openly about their experiences than people leaving incarceration sooner, or who are incarcerated in local jails or immigration detention centers. This skews the Archive toward those with long-term and life sentences.

The APWA seeks to expand representation in our collection and uplift voices of those who have been silenced. To better understand the obstacles we face, we are gathering information regarding both formal and informal restrictions to freedom of expression and information access across geographic areas and facility types. If you have information to share about these restrictions, or organizations advocating to reduce such restrictions, please contact us to let us know.

Image Credit: graphic composition, Kathryn Vitarelli; words, Mike Freedom

Archival Silences

No archive is perfectly comprehensive. We learn not only from the sources that are present, but also by critically considering archival silences and absences. What sources are not here? Whose voices are not represented? What topics may be unwritten?

Prison policies and practices limit incarcerated people’s freedom of expression, shaping prominent silences in the American Prison Writing Archive. Explicit policies allow monitoring and censoring of incarcerated people’s communications, and unwritten practices of intimidation and retaliation create a chilling effect that discourages writing openly. As the Prison Policy Initiative notes in their research on prison journalism, the limited ability to maintain personal property while incarcerated can also limit the ability to write: “Papers, notes, books, and other materials that can be important to reporting are vulnerable to confiscation and destruction by prison officials during cell searches and transfers.”

Limits on access to information, including book bans, limit the ability to consult reference materials and learn about writing opportunities. When access to periodicals the APWA advertises in, such as Prison Legal News, is limited, potential authors may never learn about the Archive. Policies and practices can change quickly and be enforced unevenly, and they differ across states, prison systems, and facilities.

Gender disparities in the APWA’s collection – featuring proportionally more writing by men than by women – in part reflect the unequal educational opportunities and resources available in women’s prisons. As the Chronicle of Higher Education has reported, women’s prisons have long been overlooked by prison education programs and frequently offer many fewer courses and programs than are available in men’s prisons. People in prisons lacking educational programs and resources may be less likely to learn about the Archive.

Differences between states are reflected in the APWA’s collection through uneven geographic coverage. For example, California and Florida have two of the largest state prison systems in the U.S. As of 2023, the APWA’s collection holds about nine times more writings from California than from Florida. Among other factors that differ from California, the Florida Department of Corrections is known for the nation’s most expansive prison book bans, banning over 20,000 titles, and also imposes privatized mail scanning, which limits privacy and access to postal mail. California also offers higher education programs in many more of its prisons than does Florida.

Even in states well-represented in the APWA’s collection, community advocacy has been necessary for incarcerated people to retain some level of access to free expression. For example, a recent policy to restrict journalism from inside New York prisons went largely unnoticed until New York Focus brought it to the attention of several national criminal justice journalism groups, such as The Marshall Project, which then acted quickly (and successfully) to advocate for the policy’s rescinding.

Silences are also reflected in the kinds of experiences reflected in the APWA. For instance, prisons may restrict or punish incarcerated people for publicly communicating about particular topics, such as prison conditions. Incarcerated people may also self-censor in order to manage potential risk to their immediate safety, release dates, parole, or future employment. People incarcerated for long periods of time may feel that they have “less to lose” by writing openly about their experiences than people leaving incarceration sooner, or who are incarcerated in local jails or immigration detention centers. This skews the Archive toward those with long-term and life sentences.

The APWA seeks to expand representation in our collection and uplift voices of those who have been silenced. To better understand the obstacles we face, we are gathering information regarding both formal and informal restrictions to freedom of expression and information access across geographic areas and facility types. If you have information to share about these restrictions, or organizations advocating to reduce such restrictions, please contact us to let us know.